Steve Wariner Celebrates Chet Atkins

By Ted Drozdowski

© 2010 CMA Close Up® News Service / Country Music Association®, Inc.

All of that was enhanced by a pure tone and remarkably clean articulation on the fretboard that seemed to come naturally. It helped that Atkins’ long, elegant hands allowed him to grab bass notes by reaching his thumb around the guitar neck to form chords physically impossible for many other players.

Still, Wariner was undaunted. “I’ve wanted to do this ever since Chet passed,” he explained, sitting in a tan leather chair in his home studio, just outside Nashville, where he recorded Steve Wariner c.g.p., My Tribute to Chet Atkins. “He was funny and fatherly and a great teacher, and I feel in many ways I owe him my career.”

Indeed, that phone call opened an important door. Atkins was impressed with a cassette of Wariner’s demos, received from Paul Yandell, a member of Atkins’ band. Yandell, a distinguished guitarist in his own right whose catalog also includes a tribute to Atkins, Forever Chet, had met Wariner on a Johnny Cash-produced session for Alive and Well, by one of the younger picker’s employers, singer/guitarist Bob Luman. Atkins soon signed Wariner to RCA Records and also tapped him to play bass in his band.

“Chet saw something in me, I guess,” Wariner said. “And he knew I needed the money, so he hired me to play, signed me to a record deal and took me under his wing.”

These two opportunities ensured that Wariner would be able to pay the bills while developing his own career. His first three singles, all produced by Atkins, failed to hit the Top 40. (“As Chet said, they started out slow and tapered off from there,” Wariner said, chuckling.) And when his first Top 10 hit came along with “Your Memory,” written by Charles Quillen and John Schweers, he continued, “Chet called me into his office and fired me from his band. He knew that I enjoyed it so much that I would never have gone out on my own otherwise.”

Since then, Wariner has made 27 albums and won three Grammy Awards, most recently in 2008 for his contribution to “Cluster Pluck,” a guitar-hero throwdown on Brad Paisley’s Play. He also co-wrote and played with Paisley on Play’s “More Than Just This Song,” another tribute to Atkins. And he has taken home four CMA Awards, winning Vocal Event of the Year in 1991 for his appearance with Vince Gill and Ricky Skaggs on Mark O’Connor and the New Nashville Cats, Single of the Year as artist and producer and Song of the Year in 1998 for “Holes in the Floor of Heaven.”

Thanks to the more than 30 Top 10 singles Wariner has celebrated, his warmly soaring alto-to-tenor voice has become as familiar to fans as his instrumental prowess. He has had many No. 1 hits including nine on the Billboard charts: “All Roads,” “I Got Dreams,” “Life’s Highway,” “Lynda,” “Some Fools Never Learn,” “Small Town Girl,” “The Weekend,” “Where Did I Go Wrong” and “You Can Dream of Me.” He has also co-written No. 1 hits for Clint Black (“Nothin’ But the Taillights”) and Garth Brooks (“Longneck Bottle”), as well as “Where the Blacktop Ends,” which peaked at No. 3 for Keith Urban.

“Steve is such a great singer, with so many Country hits, that people tend to forget what a great guitar player he is,” said singer/songwriter Bill Lloyd, half of the duo Foster & Lloyd and the former stringed instrument curator of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. “When Radney (Foster) and I shared bills with Steve, I was always impressed with his playing. He had a light, wonderful touch, and his picking hand was capable of all of the delicate and complex things Chet was known for.”

That has become even truer now, thanks to Wariner’s preparations for his latest album. “Some of these songs required serious woodshedding,” he admitted. “‘Blue Angel,’ which is rooted in classical music, was really tough. It has these crazy intervals, and Chet played it so pure, precise and fast.”

That track, written by Brazilian guitar virtuoso Natalicio Lima, was the first that Wariner cut for the new album. “Having my own studio, I was able to take my time with it,” he said. “So I analyzed ‘Blue Angel,’ tried three different classical guitars and experimented with all kinds of microphones and microphone placements until I was happy. After that, I felt like I was ready to go ahead with the project.

“I look at Chet’s career as three-tiered,” Wariner observed. “He was a great guitarist, an amazing producer and a record executive who revolutionized Nashville by building RCA Studio B and drawing on his background in jazz to change the sound of Country Music and take it to a bigger audience. Chet even had a home studio in the ’50s that was like a mini Studio B, where he’d work with artists and hone his own music. Nobody else had anything like that at the time, except Les Paul. But for me, what was most important was Chet’s own music.”

Atkins had influenced Wariner long before the two first met. “My dad had all of Chet’s records he could get,” Wariner said. “I’d sit for hours when I was a kid, slowing down the turntable and setting the needle back, trying to figure out Chet’s licks.”

“I also used that guitar for ‘Leona,’ which is named for Chet’s wife,” Wariner added. (He and Leona Atkins remained close friends up until her passing in October.) For authenticity, the gentle but boldly chiseled melody of “Leona,” written by Wariner, is framed by lush strings arranged and played by Atkins’ collaborators D. Bergen White, who had also done string charts for Wariner as far back as his self-titled 1982 album, and Carl Gorodetzky, leader of the celebrated studio ensemble The Nashville String Machine.

The album’s first three tracks nod to Atkins’ roots. Wariner’s “Leavin’ Luttrell” captures Atkins’ early playing in its thumb-and-fingers juxtaposition of delicate melody with heavy bass, inspired by Merle Travis, and fleet runs that channel jazzman George Barnes. “John Henry” is a traditional number that Atkins played when he toured with The Carter Family in the late 1940s. And Wariner used to play “(Back Home In) Indiana” as bassist in Atkins’ band.

“I think one of the reasons Chet bonded with me was our common rural roots,” Wariner said. “Chet’s brother lived not too far from Noblesville, Ind., where I was born, and my people came from central Kentucky, not too far from where Chet came from.”

Yandell stepped out of retirement to join in on Wariner’s “Reeding Out Loud,” which recalls Atkins’ freewheeling duets with the late Jerry Reed. “Steve and I were both really lucky to work with Chet and be his friend,” said Yandell. “Chet was a wonderful person and a musical genius, and Steve plays Chet’s stuff so well. He can even play ‘Blue Angel,’ which is extremely hard — and play it great. Like Chet, Steve is one of those musicians who can play anything.”

As for Wariner, his love for Atkins and his music resonates in the closing track, the elegiac “Silent Strings,” which he wrote with Kent Blazy. But despite this reflective performance, Wariner harbors more cheerful memories of his friend and mentor, who bestowed upon him his personal honorific “c.g.p.,” for “Certified Guitar Player,” a title Atkins extended only to three others: Tommy Emmanuel, John Knowles and Reed.

“When I was recording these songs I kept hearing Chet’s voice in my mind,” he reflected, his mouth curling into a smile. “‘Nice try, son,’ he’d tell me with a straight face. ‘I appreciate what you’re attempting to do.’”

On the Web: www.SteveWariner.com

CMA created the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1961 to recognize individuals for their outstanding contributions to the format with Country Music’s highest honor. Inductees are chosen by CMA’s Hall of Fame Panels of Electors, which consist of anonymous voters appointed by the CMA Board of Directors.

“Knock it off!” Steve Wariner told Chet Atkins when the legendary guitarist, producer and record executive called him one day in 1976.

“I thought it was my brother Kenny, who is a prankster,” Wariner remembered. “He’d called many times pretending to be someone else.”

But it really was Atkins. And that phone call began a friendship of 25 years, which has culminated in Steve Wariner c.g.p., My Tribute to Chet Atkins. Released on his own label SelecTone Records and produced by Wariner, this album offers 11 beautifully guitar-driven tunes inspired by and plucked from the catalog of the late six-string master, innovator and Country Music Hall of Fame member, who died in 2001.

Tackling a set devoted to Atkins is no lark, even for a musician of Wariner’s high caliber. Atkins remains one of the world’s most revered guitarists. His technique was rooted in the classic Country finger picking of Maybelle Carter and Merle Travis and extended to include jazz, classical, pop, funk and rock as well as the folk styles of France, Italy and Spain.

Chet Atkins welcomes Steve Wariner to RCA Records in June 1977. photo: courtesy of RCA Records

Steve Wariner c.g.p., My Tribute to Chet Atkins began with an erasable marker board in Wariner’s studio, on which he listed songs from Atkins’ repertoire that he wanted to record for the project. He also enlisted Yandell, who is now retired, to brainstorm that list and the intricacies of how Atkins would have approached the tunes that made the final cut.

“To really get a handle on the project, I decided to organize the album so the songs would represent the chronological evolution of Chet as a guitarist,” Wariner said.

Steve Wariner c.g.p., My Tribute to Chet Atkins illustrates the guitar wizard’s development from traditional Country picker to jazz-influenced sophisticate to classical experimenter to collaborator with Lenny Breau, Les Paul, Jerry Reed, Doc Watson and many others to consummate master. Some tunes embrace nearly all of those elements, including “Chet’s Guitar,” which Wariner wrote with Rick Carnes and recorded on a mid-’80s Gibson Country Gentleman he had received from Atkins.

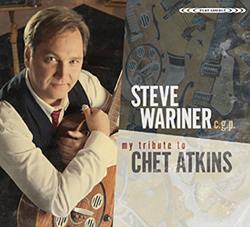

Steve Wariner c.g.p. my tribute to Chet Atkins"

photo: courtesy of SelecTone Records

Added: February 2, 2010